Early Nationalization

The creation of China as an economic entity was to take place in a series of nested stages, which would culminate in collectivization in the countryside and nationalization in the cities. Once complete, collectivized agriculture and nationalized industry would become the basic developmental seeds for the growth of a national economy. In the mythology of the era, these institutions would be the atoms that composed the new type of state, both communal and extensive. Ideally, they would form roughly consistent, standardized units of administration responsive to both local initiative and top-down planning. In reality, however, they would transform into inconsistent, autarkic nodes in a highly uneven production network.

Nationalization in the cities was originally to be completed in five stages. The first was in the seizure of so-called “bureaucratic capital” and foreign enterprises. This was already largely completed in the Northeast with the acquisition of the Japanese-built infrastructure from the GMD. These were considered to be “state-monopoly enterprises,” and they would go on to become the heart of China’s new heavy industrial sector.

In 1949, long before the First Five-Year Plan, “the new regime’s state industrial enterprises accounted for 41.3 per cent of the gross output value of China’s large, modern industries.” The new state sector, helmed by the CCP,

owned 58 percent of the country’s electric power resources, 68 percent of coal output, 92 percent of pig iron production, 97 percent of steel, 68 percent of cement, 53 percent of cotton yarn. It also controlled all railways, most modern communications and transport, and the major share of the banking business and domestic and foreign trade.[1]

But these enterprises, despite being under state monopoly, were still yoked to the capitalist imperatives of value accumulation, and were therefore understood as “state capitalist,” rather than “socialist.” Nonetheless, the conciliatory strategy of New Democracy’s controlled and ultimately curtailed transition to capitalism was essentially skipped in the Northeast.

In the port cities, many similarly large firms were not immediately nationalized. Instead, even those owned by foreign capitalists were allowed to continue operations. Over time, restrictions on firms owned by American, British or French interests were gradually increased via rising taxes and dictates “that Chinese employees could not be dismissed.” This essentially forced the enterprises’ foreign investors to continue “pouring money into China in order to keep their firms afloat, instead of to reap profits.” Because of this, the value of these firms’ shares quickly withered to worthlessness on the Western stock markets, and they either filed requests to close their enterprises and repossess whatever fixed capital the CCP would allow, or they simply abandoned their property to the communists.[2]

After this transfer of “bureaucratic” capital, the next stages of nationalization were: “(2) nationalization of the banking system; (3) transfer of private firms and factories; (4) co-operativization of handicrafts and peddlers; and (5) the establishment of urban communes.”[3] Stage two was passed through quickly. The nationalization of the banks began immediately after the completion of the Civil War and entailed the massive liquidation of most of the “446 private banks in six major Chinese cities,” as the state withdrew all public funds from private financial institutions, transferring them to the People’s Bank. Within less than a year, “233 banks, constituting 52 percent of the total, were closed.” Those that remained were quickly merged into larger “joint” operations which were, in reality, administrative units of the central bank. The nationalization of the banking system was complete by 1952.[4]

The third and fourth stages of nationalization—the transfer of private firms and factories—were the most drawn-out and also the most crucial. The nationalization of private enterprises “involved three million private firms and factories and directly affected an urban population of seventy million,”[5] basically restructuring the industrial organization of all major Chinese cities, though the large, commercially-oriented port cities bore the brunt of this. This was also the phase of nationalization that aimed to curtail and ultimately halt the transition to capitalism unleashed in the New Democracy period, since it targeted the larger private enterprises perceived to be the vanguard of that transition.

Private enterprises first passed from fulfilling state contracts to becoming official joint (state-private) enterprises, in which production was no longer guided by contracts but instead by state-planned targets, and ultimate authority in the enterprise was transferred from the investors and owners to the state. Government orders as a percentage of total private industrial output rose from a mere 12% in 1949 to 82% by 1955. In order to soften backlash by the former owners of these enterprises, the state agreed to reimburse them at a fixed rate of interest out of future revenue.[6]

In private commercial enterprises (those specializing in the distribution of goods) the transformation was slower. Meeting production targets was easy enough, but replacing the complex market structures created by value-seeking firms with a functional state-directed distribution system was another task entirely. As we have seen, state commercial networks were piloted in the countryside and the northeast. But it was not until 1953 that the state began to transform wholesale trade into “state commerce,” even then transferring only the largest private commercial enterprises to state ownership, retaining the same merchants and employees, each largely doing the same work.

Whereas the third stage of nationalization saw the complete restructuring of most medium-to-large urban industries, the fourth aimed at a complete reinvention of Chinese industry as such, beginning at its rural roots. In most of China’s major cities, and in nearly all of its rural areas, production was dominated by small enterprises. Loosely understood as “handicrafts and peddlers,” these small workshops or retailers constituted the decentralized backbone of Chinese day-to-day production, and were primary to the distribution of basic goods across China’s rural interior. According to government statistics, even by 1954 there were still “about twenty million people […] engaged in handicrafts on an individual basis and the value of their production was about 9.3 billion yuan […] accounting for about 17.4 percent of the country’s gross output value.”[7] In handicrafts, the tools and other means of production were owned by the individual producers.

Private handicraftsmen were encouraged to join “small supply and marketing groups,” then “supply and marketing co-operatives,” and, finally “producers’ co-operatives,” all of which would fill orders for the state commercial establishments. In these co-ops, handicraftsmen would first retain legal ownership of their tools and products, then begin pooling labor to obtain cheaper raw materials and to market products, and, finally, pool their own profits and collectively manage reserve and welfare funds. This transformation spanned the New Democracy era and the beginning of the First Five-Year Plan, with handicraft co-op membership increasing from 89,000 in 1949 to 250,000 in 1952. By the end of 1955, this number had increased to about 2.2 million, but still only encompassed “29 percent of the total handicraftsmen in the country.” Finally, in 1956 a nationwide campaign was launched to systematically organize artisans into larger co-ops, and the membership jumped from 29% of all artisans to 92% by the end of the year.[8]

Origins of the First Five-Year Plan

The completion of the third and fourth stages of nationalization undercut all previous mechanisms for the distribution of goods by destroying both modern capitalist markets and the mercantile networks of the region’s (largely rural) handicraftsmen and peddlers. Without the law of value guiding the distribution of goods, the location of investment and the movements of people, the Party and the new state were seen as the only alternative forces capable of large-scale coordination. As the transition to capitalism was intentionally slowed, the Party directed the skeleton of the central state to take over the basic functions of production, initiating a new round of national development guided by the planning structure piloted in the Northeast. This began the fusion of Party and state, and it is here that the class structure of the socialist era begins to take root.

In the Northeast, there had initially been wariness over the turn to comprehensive economic planning. Though planning was possible earlier, the regional leadership “relied upon a loosely co-ordinated contractual relationship to manage the economy”[9] until 1951. Gao Gang, one of the regional Party leaders, expressed considerable wariness at the lack of expertise and statistical data available, as well as the absolute limits inherent in the very idea of a national plan. He maintained that “we are not God, and we cannot work out a perfect plan.”[10]

Nonetheless, he had strong trust in the Russian system and spearheaded the effort to develop a more comprehensive economic planning infrastructure, directing the regional Party to collect industrial statistics and reshape the top-down administrative system to include “frequent consultations and exchanges of information at various levels in the hierarchy,”[11] resulting in plans that were centrally developed, but also kept in check according to what enterprises were actually capable of. The work of planning was rationalized with the invention of a standardized accounting system during the New Record Movement, and administration was standardized through the implementation of the “responsibility system” and “one-man management,” which created interlocking hierarchies headed by the factory director.

These new systems, despite consultation among administrative levels, however, were not enough to prevent the irrationalities that came with the incentive to report false production numbers in order to satisfy a distantly-mandated plan. Waste and inefficiency became commonplace. As early as 1951, the Northeast regional leadership “began to introduce the mobilizational approach, which allowed workers to participate in the formulation of annual plans and the supervision of their enforcement.”[12] Even with widespread worker involvement between 1951 and 1953, however, overtime was extensive, with workers suffering and machinery being worked to its breaking point. A better-rationalized planning infrastructure, even one with high levels of direct worker control, was in no way a solution for the basic problems of poor equipment and lack of trained personnel.

In the same period, new wage systems and technical training were devised with the help of Russian technicians, and the machinery was modernized. The methods of industrial organization piloted in the Northeast would later become known as the “Soviet Model,” in competition with the “Shanghai” or “East China Model” common in the port cities. But what scholars often classify as the “Soviet Model” actually covers two alternating tendencies in industrial organization and enterprise management, the first influenced by High Stalinist methods of mass mobilization campaigns alongside “crash production drives and close supervision by Party committees,” and the second more in line with the USSR’s five-year plans of the 1930s, a method of organization “encapsulated in one-man management” which “in effect imposed a strict hierarchical and bureaucratic order over enterprises that was antithetical to the mobilizational impulses of High Stalinism.”[13] The “Soviet Model” built in the Northeast, then, was itself riven with contradictions, each opposing tendency theoretically justified by different periods of Russian industrialization.

The experiment was not only based on prevailing theories of non-capitalist industrial development drawn from the USSR, it was also built with the direct participation of thousands of Russians. The Northeastern province of “Liaoning alone was the location for over one-half of all the Soviet aid projects [and] a minimum of 10,000, perhaps as many as 20,000, Soviet experts and industrial advisers worked in China during the 1950s.” Meanwhile, “At least 80,000 Chinese engineers, technicians, and advanced research personnel were trained in the USSR.”[14] This placed such technicians in a de facto position of central authority, and raised the question of what role the CCP should play in the workplace.

Early on, each enterprise’s Party committee remained formally separate from the technical management, tasked mostly with “supervision and guarantee” of the work. This entailed leading mobilization campaigns, supervising the enforcement of policies, promoting the relatively democratic forms of management common at the time (usually in the form of “a congress of workers and staff or a factory management committee”), as well as overseeing training and promotions. Factory directors were often not members of the Party. “One-man management” was therefore never practiced in its purest form, as numerous checks existed against the directors’ executive decisions.

This meant that, instead of the “one-man management” laid out in Party handbooks of the time, most enterprises had a dual power structure, divided between Party and technical leadership, each deeply rooted in widespread practices of worker self-management and each offering its own new form of upward mobility. The very theory of one-man management would quickly become a point of contention as the Northeast’s experiment was extended to the rest of the country in 1953.[15] The resulting industrial structure, though inflected with various Soviet characteristics, quickly took on a character of its own.

Extending the Soviet Model

Not wanting to slide back into capitalist transition, many saw the forms of centralized economic planning, Taylorist rationalization and promotion of heavy industries advocated by the Russians to be the only feasible option. The “East China Model” of industry in the port cities, though functional at the level of individual enterprises, had developed no method for larger-scale coordination short of value-based mechanisms such as markets. The Northeast offered the only experiment in an ostensibly non-capitalist direction, despite a general wariness of over-reliance on Soviet theory, aid and technical expertise.

In 1952, Gao Gang, already one of six chairmen of the State Council, was promoted from the Northeast regional Party leadership to become head of the State Planning Commission, where he was given responsibility for completing the design of the First Five-Year Plan. The plan was intended to extend the gains of the Northeastern industries nationwide by founding new industrial centers outside of either the port cities or Manchuria and by knitting together the fragmented, multinational country into a unified and standardized economic fabric.

The new state’s planning infrastructure was composed of a complex tier of nested ministries and bureaus, overseen by the State Council or ever-changing variants of state planning commissions. The ideal planning hierarchy was optimistic, at best. In reality, its upper echelons underwent nearly constant administrative changes throughout the First Five-Year Plan, while the lower ministries and bureaus were tasked with yoking together productive units of myriad sizes and structures, each using various forms of labor deployment. At the same time these bureaus were somehow expected to quantify and rationalize the productive output of this industrial miasma. The period was marked by “twin peaks” of activity, one in 1953 and another in 1956, in which such organizational change was especially rapid.[16]

Nonetheless, in these years it is arguable that, in certain regions, the CCP managed to operationalize the “Soviet Model” to an extent unprecedented in either Manchuria or the USSR. But this does not mean that we can take the theory behind the original Soviet Model or its variants as accurate descriptions of how Chinese industry functioned. This is the major error of existing literature on the subject, whether laudatory[17] or critical.[18] The truth is that even when the Soviet Model was ascendant the deployment of any such model was deeply uneven and contradictory.

It is partially correct to argue that the Soviet Model, with its base in the Northeast, was in constant contest with the East China Model based in the port cities. Over time, each mutually transformed the other, and both were challenged and periodically revolutionized from the bottom-up by worker revolts, reaching high points in the mid-1950s and late 1960s. Even this bipolar model, however, is too clean-cut, failing to account for the novel divisions that arose from the collision of these two systems. Even the term “model” attributes too much intent to the development of these systems which were in reality haphazard adaptations cobbled together from the materials at hand.

Nonetheless, this division provides a workable framework, if we understand the two “models” as the material cores of two industrial systems with different gravities, each pushed along a separate trajectory by its own inertia, though also affected by the pull of its sibling system. These systems had gravitational cores in their respective cities and regions, but these cores could only exert any “pull” because they operated across the field of China’s agricultural “ocean,” from which they drew their grain surplus. The gravity of these systems, then, was not purely metaphorical, but took shape in the very real ratios at which grain was siphoned from the countryside into the industrial cores.

In the Northeast, the Soviet Model’s center of gravity, the inheritance of large-scale heavy industrial infrastructure built by the Japanese required high-level management, strict divisions of labor, extensive data collection and standardized forms of administration to be applied to standardized factories and logistics networks. The influx of Russian technicians and Soviet assistance for the modernization of these factories only exaggerated these features, and the Party’s focus on this model in the mid-1950s amplified its gravity.

Prior to this, the East China Model had been more dominant in national policy, due to the Party’s focus on rebuilding the port cities through international investment. This model had inherited a diverse mesh of industrial enterprises, with several large-scale firms afloat amidst a mass of medium and small workshops coordinated via markets and networks of lineage, patronage and more amorphous forms of fraternity. It had also inherited stronger vestiges of the imperial era and the subsequent period of warlordism, including powerful local elites, violent street gangs, arcane labor guilds and millions of peddlers, handicraftsmen and other micro-units of production and distribution. This required more nuanced, localized forms of management, the ability to cope with fluctuating demand for labor, the accommodation of older traditions, the creation of organs capable of coordinating production among units of varying sizes and styles, and the simple ability to account for what was being produced and what was not.

The First Five-Year Plan (1953-1957) marked the tentative ascendance of the Soviet Model against the East China Model, which had predominated during the New Democracy era. In purely economic terms, the result was one of the most profound and extensive phases of industrialization ever seen. National income doubled between 1949 and 1954 and more than tripled by 1958.[19] Each year between 1952 and 1957 saw industrial production expand by an astounding 17% as “virtually every sector of the economy was rehabilitated, and the groundwork for sustained future growth was laid by massive investments in education and training.” This made possible “rapid social mobility, as farmers moved into the city and young people entered college.” For decades after, the period would be remembered nostalgically as a sort of golden age for urbanites, marked by peace, progress and prosperity. [20]

In allocating investment, the Plan entirely replaced price incentives with “quantity” measures decided by the planners themselves in a process called “material balance planning.” Though prices, profits, wages, banks and money still nominally existed, “the financial system was ‘passive,’” meaning that “financial flows were assigned to accommodate the plan (which was drawn up in terms of physical quantities), rather than to independently influence resource allocation flows.” Features of the old financial system, such as prices and profits, were now “used to audit and monitor performance, not to drive investment decisions.” In its ideal form, “material balance planning” would allow a planner to “use an input-output table to compute the interdependent needs of the whole economy.” [21]

In reality, however, the system’s complexity and unevenness prevented planners from ever approximating this ideal. Planners

[…] divided blocks of resources among different stakeholders, drew up their own wish lists of priority projects and the resources they needed, and then allocated anything left over to the numerous unmet needs. The foreign sector could be used as a last resort to make up for scarcities and sell surpluses.[22]

The plan’s focus on industry at the expense of agriculture, then, was fully intentional. Between 1952 and 1958, “of the total capital investment, 51.1 percent went for industry and only 8.6 percent for agriculture,”[23] with the total investment in “capital construction”[24] increasing from 1.13 billion yuan in 1950 to 26.7 billion in 1958. The net output value of consumer goods saw a similar shrinkage relative to industry in the same period.[25]

This disproportion was also geographical, with the plan designed to “move the industrial center of gravity away from the coastal enclaves,” by dictating that nearly all of the 156 planned large industrial projects were to be “built in inland regions or in the Northeast,”[26] with 472 of all 694 industrial enterprises, large and small, “to be located in the interior.”[27] Severed from global markets and limited to a small slew of socialist trading partners—namely the USSR, which accounted for half of all international trade during this period[28]—the focus on the interior also aimed to “build new industries closer to sources of raw materials and to areas of consumption and distribution.”[29]

At the same time, the elimination of the handicrafts industry and the market networks that had undergirded relations between city and countryside ensured that most of China’s industrial activity was now urban, and that the population would be more strictly concentrated in urban industries or dispersed across the agricultural collectives being created at this time. Most importantly: the divide between urban and rural was now becoming a clear geographic divide between grain-producing and grain-consuming regions, with the grain-consumers as the primary targets of industrialization.

Much of this industrial build-up, however, was ostensibly geared toward the production of agricultural producers’ goods. The state “bought agricultural commodities […] cheaply from the countryside […] and exchanged high-priced industrial goods.”[30] The goal was as much to modernize agriculture as it was to build a powerful industrial base. But, having culled the countryside of much of its independent industry and the trade networks that accompanied them,[31] the First Five-Year Plan failed to provide the rural sector with a fully workable infrastructure capable of replacing what was lost.

Lacking road, rails, electricity, and access to petroleum products, much of the Chinese countryside required enormous national investment just to make modern technologies such as tractors and electrified food-processing or fertilizer plants functional. But this presented central planners with a catch: in order to invest in this sort of infrastructure, urban industry needed to be built up, but in order to build up urban industry, agriculture needed to be modernized to feed the growing industrial workforce, largely composed of new migrants from the countryside.

The central planners’ solution to this aporia was not to slow the process and implement modernization piecemeal—a politically unfeasible option when the possibility of renewed global war was still a salient fear—but instead to intensify extraction of surplus from the peasantry, force more workers from former handicrafts into agriculture and introduce “intermediate” technologies to agricultural production that required less infrastructural support and less technical prowess. Ultimately, this would also entail constraining rural-to-urban migration through the implementation of strict administrative controls on population movement.

Tiers

During this same period, the state and industrial bureaucracies swelled, job titles and wage-grades proliferating even while de facto hierarchies rarely matched the official plan. Enveloping the growth of industry itself, the bureaucracy of the Party and the new state (still marginally separate) was the top growth sector between 1949 and 1957. Large state bureaucracies had been hallmarks of both the Japanese industrial structure and the GMD’s own state-led production, but the scale of the new state far exceeded its predecessors. Whereas the GMD’s bureaucracy had peaked at 2 million state functionaries in 1948, the new state saw cadre numbers skyrocket from 720,000 in 1949 to 3.31 million in 1952. And this was only the beginning: “Within less than a decade, from 1949 to 1957, the cadre corps increased tenfold both in absolute number and in percentage of the population—to 8.09 million and from .13 to 1.2 percent of the population.” [32]

The state’s own reproduction became increasingly expensive: “by 1955, government cadres were eating up nearly 10 percent of the national budget, almost twice the 5 percent ceiling the national leadership had originally planned.”[33] This direct cost was largely in the form of wages paid to cadre, and these wages both increased and became more stratified according to rank.[34] The increasing costliness and complexity of the state bureaucracy was paralleled in the industrial sectors, as workers’ own wages underwent a series of reforms. As national investment poured into heavy industry, the already existing divergence between rural and urban incomes became solidified into state policy. At the same time, urban wages were themselves cut into numerous grades, though it was rare that actual wage distributions matched the grades laid out in the plan. While high-ranking cadre clearly took in the highest incomes, technicians and intellectuals were supposed to be given significant privileges in this period relative to other urbanites.[35]

Among urban workers, there was an attempt to implement a wage hierarchy that emphasized the priorities of the central state’s investment strategy. In this plan, workers employed in heavy industry would see the highest wages for manual laborers, with the highest-grade workers in these categories making slightly less than the pay of mid-level cadres such as bureau section chiefs, and basically on par with the pay of university lecturers and assistant engineers. Lowest-grade heavy industrial workers, however, would only make slightly less than the average for primary school teachers. This signals that the wage tiers designed by the Party were intended to exist not only between industrial classifications within the cities, but also within the factories themselves.[36]

The actual income of urban workers did, in fact, increase some 42.8% between 1952 and 1957, but this increase was not distributed evenly across occupations. Production line workers saw the implementation of “a complex series of individual bonuses and rewards paid in addition to salaries.” In “joint” enterprises (i.e., newly nationalized enterprises, mostly in the port cities) wages actually fell, as in Shanghai, where “workers in newly nationalized textile mills saw their real incomes drop by 50 to 60 percent,” a loss only partially compensated for by an increase in welfare benefits.[37]

Many industries, plagued by poor production statistics and chaotic practices on the ground also implemented piece-rates for individual workers: “By 1952 over one-third of all industrial workers were on piece-rate systems and by 1956 the percentage had climbed to 42 percent.” Aside from wage grades for factory level cadre, there were additional ranks for “service personnel,” eight ranks for “technical personnel,” and five for “technicians,” four for “assistant technicians” and an entire host of “bonus payments to managerial and technical personnel at all levels of the industrial system when targets were met or overreached.”[38]

These wage grades, bonuses and piece-rate hierarchies corresponded to the attempt to rationalize Chinese industry, building new model factories along the lines of the Soviet Model and force-fitting pre-existing practices in the port cities into industrial units that would parallel those of the Northeast. But, again, the ideal form of the Soviet Model never materialized. Not only were there tensions between the dual hierarchies of those with technical versus political privileges within the factory, there was also the simple absurdity of trying to coerce the port cities’ industrial miasma into a single, rationalized model designed originally to fit the needs of heavy industry.

Toward the end of the 1950s, Chinese planners began to realize that “the system did not suit Chinese conditions technically, economically, or politically.” The amalgamation of tens, if not hundreds of thousands of small handicraftsmen, workshops and factories into large-scale industrial enterprises created a logistical nightmare in many cities, causing wide-ranging “conflicts over value assessment and compensation” as well as “problems concerning personnel and managerial authority,” in which the “managers, owners, and technical personnel” from the old plants competed to see who “would have what responsibility and powers in the new set-up.” [39]

More importantly, the intricate wage hierarchies based on skill, industry and relation to the state never materialized. Though the grades were laid out in perfect detail, they never corresponded to the actual trends in wages and benefits observed in the period. Some of the divisions incentivized by the central state did, in fact, deepen, as was the case with the privileging of workers in state-owned heavy industries, versus underfunded collective enterprises, which employed more temporary and contract workers. But other hierarchies, such as wage grades based on technical skill, were never implemented in their intended form, despite propaganda to the contrary. What did materialize were chaotic new hierarchies, new relations to the state and new forms of subsistence, many of which, though novel, could trace as much of a lineage to pre-revolutionary Chinese institutions as they could to Soviet ones.

In these new hierarchies, certain regions were privileged over others. The port cities suffered from inadequate funding and an industrial structure that bore little resemblance to the one presumed by central planning directives. This resulted in a need for numerous, short-term fixes, many of which inadvertently became the foundation for new, long-term configurations of power and methods of production. Among the most pressing problems was the risk of inflation. As wages increased, the CCP feared the rise of a new inflationary cycle similar to the one that had crippled both the Japanese and GMD regimes—and the first “peak” of rapid investment in 1953 did, in fact, begin to reignite inflation.[40] In response, local governments were encouraged to provide alternatives to monetary wages. This resulted in many enterprise managers reviving practices initiated by previous industrializers, be they warlord, Nationalist or Japanese, all of whom had sought local fixes to inflationary chaos during wartime by internalizing the reproduction of labor within the factory through the direct provision of things like food, housing and medical care without recourse to the market.

Labor Without Value

The CCP’s new welfare institutions, then, actually traced their histories to previous short-term, local, and often independent solutions more than to any central state directive for the provision of benefits: “workplace welfare as an institution had developed independently in Chinese cities, during the hyperinflation of the 1940s. CCP efforts to stamp out inflation were facilitated by continuing the practice of having factories provide food and other basic necessities to workers.”[41] This was the beginning of the danwei, or “work-unit,” system, which would soon expand to the entirety of Chinese industry. In this system, “the new regime exercised power through the penetration of basic units in society, including factories and other enterprises,”[42] simultaneously reducing labor turnover, staving off inflation, and making workers directly dependent on the central state’s enterprise-level allotments of resources, rather than monetary wages.

This relationship between workers and the state would become one of the most definitive features of the socialist developmental regime, which increasingly managed labor as if it were a component of the factory itself. Resources for labor reproduction, rather than being packaged in the wage, were instead drawn from so-called “Capital Construction Investment” (CCI) funds originally intended for the purchase of new machines and the construction of factory complexes. Total CCI “rose from 2.9 billion yuan in 1952 to 10.5 billion yuan in 1957,” consistent with the Five-Year Plan’s focus on the expansion of industrial facilities. But over the course of the 1950s increasing amounts of these investment funds began going to “nonproductive CCI,” which entailed “projects such as the construction of residential units, hospitals, and other facilities that did not directly contribute to economic output.” Between 1951 and 1954, such nonproductive (or, more accurately, reproductive) projects ate up more than 50% of total CCI.

The First Five-Year Plan, then, was deceptive. In reality, the construction of new reproductive institutions was just as integral as the prioritization of heavy industry. These institutions created new interfaces between workers and the state and facilitated new methods of social control. Meanwhile, the reproduction and control of workers was, in practice, treated as contiguous with or identical to investment in factories as such, with welfare not managed or distributed at the national, provincial or even local government level, but instead at the level of the industrial enterprise, just like investments in plant and machinery.

This arrangement effectively forced the state to draw an absolute surplus from industry, if only to sustain these welfare payments. But it also ensured that this surplus could never evolve into surplus value, due to its increasing detachment from the wage and the near-total lack of anything resembling a labor market, preventing labor-power from constituting itself as a commodity even while labor as such was treated by planners like any other producers’ good.[43] Meanwhile, this absolute surplus in industry was in fact a surplus drawn from a surplus, with the product of industrial workers always only a secondary derivation of the surplus extracted from agricultural laborers. Grain was always the primary productive engine of the socialist regime of accumulation, and its alchemical transformation into steel was the surplus product of the system’s net grain consumers—the industrial workforce.

Other novel hierarchies formed within this industrial workforce, as well as within individual danwei. Proximity to the central state and the prioritized heavy industrial sector was one such hierarchy, with those “at the periphery of industrial employment, in the vast urban handicraft sector” receiving “the lowest pay and only meager welfare benefits, if any.”[44] But all were effectively hierarchies in the distribution of the absolute grain surplus extracted from the peasantry or from non-human environmental processes (in new waves of deforestation and frontier settlement, for instance).

In contrast, the hierarchies based on technical skill intended by central planners never actually took shape. During the 1950s in industrial centers such as Shanghai, “there was little distinction in pay between skilled and unskilled workers.”[45] The state could not determine wages for workers, even at state-owned enterprises, due to the sheer enormity of the task. Over the course of nationalization, “PRC officials gained control of the wage bill for over 7 million industrial workers nationwide,”[46] forcing the state to allow individual ministries to determine their own pay rates and enterprises to implement them.

But this implementation was rarely consistent with the rates determined by these ministries. Enterprises were given a set wage bill by planning authorities, and workers in the enterprise were frequently allowed to wield considerable influence in the distribution of this sum. Here the High Stalinist aspects of the Soviet Model were in strong evidence, with wages not set by factory directors, per the “one-man management” system, but instead set in mass mobilizational wage adjustment “campaigns,” in which “workers openly discussed and debated among themselves who was deserving of wage promotions and who was not.” The result, in the vast majority of cases, was that these meetings “tended to steer wage hikes toward relatively older workers with larger families to support,” thereby creating an “informal seniority wage system” which would persist throughout the socialist era, reinforced by the cultural affirmation of older workers who had suffered in the pre-revolutionary labor regimes, and who often considered younger workers to be spoiled by the relative prosperity of socialism.[47]

In addition to the growing division between old and young workers within the factory, the family network resurfaced as a prominent form of labor allocation and surplus distribution. With the breakdown of the labor market and the fixing of workers through the danwei, and, later, the hukou, system, enterprises had to turn to central industrial ministries to expand their workforce. The problem of labor turnover was effectively solved by constraining workers’ ability to migrate to different cities and by tying pension eligibility to years worked at a given enterprise—again reinforcing the hierarchy of seniority. The difficulty of acquiring new workers encouraged enterprises to hoard labor, even during economic downturns, but the inability to recruit “from society”—i.e., to freely hire unemployed urbanites or rural migrants—put strong geographical constraints on the available labor pool.[48]

The easiest solution to this problem, adopted as a local fix by enterprises across the country, was the practice of “replacement (dingti),” in which the enterprise would hire relatives and children of current employees into the same work unit. Because of the constraints on hiring, “the Chinese government inadvertently promoted an intensely localistic practice of work-unit occupational inheritance.”[49] In so doing, the CCP revived the family unit as an integral source of social privilege, fusing it to the danwei and thereby to the state itself. Families that had poor placement or little clout in their enterprises held little bargaining power and therefore saw their family members deported to far-off cities (often in the interior) by the demands of national labor allocation. This created a financial and emotional stress that further prevented such families from ascending the distributional hierarchy.

Even the inter-enterprise coordination developed later in the 1950s did not correlate to the structure laid out in the Five-Year Plan. Outside of the Northeast, industrial ministries were forced to devolve significant amounts of power to local officials. In Shanghai and Guangzhou, this resulted in the inflated importance of Industrial Work Departments (gongye gongzuo bu) relative to their assigned functions. Ostensibly a minor institution under the direction of the Municipal Party Committee, these departments ultimately “played a critical mediating role in the translation of central political and administrative directives into actual practice within industrial plants […] and would eventually take over most supervisory functions of certain factories within their cities,” despite their having been assigned no such role in the smooth hierarchy envisioned by planning authorities.[50] In the late 1950s, this decentralization would take on extreme forms.

Collectivizing Rural Labor

All of these changes in the cities, however, were undergirded by monumental transformations in the countryside. At the same time as the implementation of early nationalization and the first Five Year Plan, rural production was collectivized in four stages stretched across the 1950s. The first two stages involved the formation of “cooperatives,” while the latter two would involve the formation of “collectives.” During the land reform movement, mutual aid teams of six or more households had formed with the aim of assisting in production on individual farms. Although guided by the Party, this was largely a local and voluntary response to the fact that farm implements, most notably work animals, had to be divided between households as they were taken from landlords. These mutual aid teams were seasonal, usually coming together at times of harvest and planting, and they allowed the smallholding economy to be “economically viable” by sharing scarce resources.[51] Supply and marketing cooperatives were also set up, this time by the Party, as it competed with local merchants in the drive to gain control over surplus output. A mutual aid team, for example, could receive inputs such as fertilizer from one of these cooperatives in return for a specific amount of grain. In turn, the supply and marketing cooperatives put pressure on peasant families and offered incentives to further collectivize.[52] These co-operatives were integrated into the unified purchasing and marketing system beginning in the fall of 1953 as private merchants were forced out of the agricultural market.

In 1954 and 1955, during the second stage of collectivization, most mutual aid teams were converted into “lower agricultural producers’ cooperatives,” consisting of groups of about 20 households. A view within the Party had emerged that a higher level of cooperation was needed so that it would be easier to organize unused rural labor, especially during the slack season. If the process was too slow, it was thought that new inequalities would take root as some households or mutual aid teams gained resources at the expense of others, and by the mid-1950s reports of inequalities were emerging.[53] These opinions became a major driving force within the Party, both at the center and in the countryside, for further collectivization through the GLF.

Though guided by the Party, the cooperatives were not simply imposed upon the peasantry. Financial credit and technical aid were offered as incentives to join,[54] and there is little indication of major resistance at this stage as peasants still maintained ownership over their means of production and land, both of which were now used collectively but still technically owned by the households. Crops were divided according to contributed labor and land. The exact method of calculating this remuneration was difficult and varied by place, although the Party preferred systems that stressed the contributions of labor over property.[55]

Individual labor contribution was counted in “workpoints.” Lasting until decollectivization in late 1970s, the workpoints system was complex and constantly changing. Different numbers of points were assigned to different jobs, usually averaging around 10 points for a man’s full day of labor, and 8 for a woman’s. Under the cooperatives, a peasant’s total workpoints were exchanged with the collective at the end of the year for grain, other products and cash. Their “value” was “arrived at by dividing the collective’s total net product (after collective funds and accumulation) by the combined workpoints of all the members.”[56] The complexity of this remuneration problem probably contributed to the demise of the cooperatives.

While only 2% of rural households were members of cooperatives in 1954, by the end of 1956, 98% had joined. This year marked a rapid acceleration in the re-organization of rural life.[57] But the production of agricultural surplus was growing slower than expected and, due to this, disagreements within the Party began to emerge concerning the speed of rural transformation. Mao and others pushed for a more rapid shift, despite the lack of an industrial base that could provide for the mechanization of agriculture, since they regarded the slowing growth of agricultural production as a roadblock to rapid industrialization. The majority of the CCP Central Committee seems to have been worried that too rapid an expansion of cooperatives would be disorderly and potentially lose the support of the rural masses. This temporarily slowed the process in early 1955 before Mao pushed successfully for a more rapid process in the summer of that same year. While both sides of the debate used the issue of rising class differentiation as evidence for their own position, they both also shared a primary concern with rural productivity and the state control over surplus. At issue was how to best secure gains in agricultural production.

From 1956 to 1957, in the third stage of collectivization, these the “lower-stage” producers’ cooperatives were turned into collectives, called “higher agricultural producers cooperatives,” in which individual households gave up their ownership of land, livestock and agricultural implements to collectives of between 40 and 200 households.[58] There was more resistance at this stage, though how much is a matter of debate, and the Party was more coercive in pushing this process as well. Under this system, returns were divided solely according to one’s individual labor contribution and livestock, implements and land was collectivized. In response, many peasants seem to have consumed many of their livestock as a rational form of resistance. The larger size of these collectives made it easier for the state to procure the agricultural surplus it needed to feed the cities as there were far fewer units from which to extract.

In 1958 the Great Leap Forward (GLF) began with the emergence of even larger collectives called communes—the fourth and final stage of collectivization. These rural communes encompassed a marketing town and its surrounding villages, with tens of thousands of members. The commune form was not planned from the beginning, but emerged in certain areas in response to local conditions and the need to deploy a larger labor force for massive infrastructure works, especially irrigation and reservoirs. Lower-level cadre were a driving force in the process. Peasants were often moved long distances and remained away from their home village for months at a time. Only after the phenomenon had emerged locally was it recognized by the state as part of the GLF. This recognition, in turn, led to the spread of the commune form across rural China. The communes came to be portrayed as part of a quick “transition from a socialist society to a communist one,” both domestically and internationally (as part of the growing competition with the Russians). In August of 1958—after the form began to appear in the countryside—the Central Committee passed a resolution on the People’s Communes, stating, “The realization of communism in our country is not far off. We should actively exploit the People’s Commune model and discover the concrete means by which to make the transition to communism.”[59]

In the 1950s, especially during the GLF, the realization of communism in the countryside also meant rural industrialization. A key slogan of the period was “walking on two legs,” meaning that large-scale capital-intensive urban industries should develop alongside labor-intensive low-capital primarily-rural ones producing for the agricultural sector.[60] While the traditional system of rural handicraft industry had constituted an “organic link between growing and processing agricultural product”—much of which would then be sold into the urban market—this “organic link” had been cut by the state purchasing system.[61] Household incomes in areas that had specialized in handicraft production dropped as collectivization began.[62] Yet collectives and especially communes during the GLF maintained and even expanded rural industrialization. Agriculture was to be technologically modernized not by the import of urban industrial inputs but instead by low-tech local production, a process of self-reliance. The countryside had to mobilize its own labor for its own development, all while much of its surplus was being extracted by the state for urban industrial development.

This also meant mobilizing and diverting rural (primarily male) labor into non-agricultural production, supplanting many of the old handicraft industries that still operated within rural households. Seven and a half million new factories were set up in less than a year at the beginning of the GLF.[63] In the winter of 1957-1958, as many as 100 million peasants worked in irrigation and water conservancy projects.[64] Most famously, backyard iron and steel factories sprung up all over rural China in response to a call to have industrial production surpass agricultural production—a call that was taken as a target for all localities, not just a national target. This diversion of labor did not only occur during the slack season. Farm labor declined as a share of total rural employment during the GLF, and output soon followed. While initial estimates showed that agricultural yields in 1958 were double that of the year before, these turned out to be false, and by the summer of 1959 they were revised downward by one third.[65] With the diversion of workers out of agriculture, harvests were neglected and food rotted.

The distribution system (fenpei zhidu) was again modified so that what little was left of the private economy was completely suppressed. Up until the GLF (and throughout all three early stages of collectivization) peasant households had maintained private plots adding up to about 10% of total arable land. These were abolished during the GLF, though they would soon return in the retrenchment of the 1960s. Although absent for only a few years, the suppression of these private plots had a crucial importance, since they acted as a last buffer against famine. Likewise, the last of the private markets in grain and agricultural goods disappeared. A “free supply” system (gongjizhi) overtook remuneration according to labor (gongzizhi), with basic necessities provided to all commune members in many, but not all, communes.[66] Communal dining halls, which became a key component of distribution, emerged from below in many communes even though it was against Central Committee regulations.[67] With the Party playing catch up, Mao stated in August 1958, that “when people can eat in public dining halls and not be charged for food, this is communism.”[68] The practice of free distribution spread from commune to commune, with Mao mouthing support. The resulting system, however, spread unevenly and, eventually, it was unstable as well. Communes ignored regulations and adopted different levels of free supply, from grain, to meals, to all basic necessities.[69] Poorer communes adopted mixed distribution systems, with some goods being linked to labor and others not. Most retained some degree of payment in workpoints.

Like the patriarchal family farm, a gendered division of labor was central to the management of rural labor under the communes. As male labor moved into sideline work, women increasingly took over farming, where their labor was usually allocated fewer workpoints than male agricultural labor.[70] At the same time, women’s reproductive work was never fully remunerated. Under the higher agricultural producers cooperatives, women worked in the fields during the day for workpoints and at home producing clothing for their families at night, for which they were allotted no additional workpoints. Women’s handicraft labor, which had brought in money for the household in earlier times, was now more invisible than ever.[71] During the GLF there was some socialization of women’s reproductive labor, most notably in the form of the collective dining halls, but the state did not put resources into these changes nor push communes to do so, and women continued to work more hours, much of it unpaid.[72] This unpaid labor was foundational to the state accumulation strategy.[73]

As the system of dining halls spread from commune to commune, so too did the competition for production. With “politics in command” and planning replaced by decentralized targets, claiming higher production was a way to show one’s good politics, and the incentive to lie about production grew. But as communes inflated their production figures, the state increased its extractions and it also moved more rural labor into the cities. Compared to 1957, state grain procurements rose by 22% in 1958, 40% in 1959 and by 6% in 1960.[74] Combined with the diversion of rural labor into sideline production of steel and other non-agricultural projects, agricultural production no longer met demand.

The collective dining halls and the huge size of communes made it almost impossible for peasants to see how their labor affected their own subsistence. The accounting and workpoints systems had basically broken down. As crop yields dropped in 1959, food began to run out in the dining halls and peasants stayed home to conserve energy.[75] Collective control over labor disintegrated. Most free dining halls only lasted three months, and in the fall of 1958 even commune cadres’ salaries were stopped.[76] Meals in the dining halls that continued to exist in 1959 had to be purchased with meal tickets given out according to work.[77] By the spring of 1959, the Central Committee tried to push the communes back into a system of remuneration according to labor: “The principle of distribution according to labor means calculating payment according to the amount of labor one does. The more work done, the more one will earn.” And summer harvests were to be distributed with 60 to 70% according to labor.[78]

While the initial rollback had already begun, famine began to strike that spring. It wasn’t until 1960 that the free supply system was again put on hold, this time permanently. In June, regulations on commune distribution stated that “production teams must conscientiously implement a system of distribution according to labour, with more pay for more work, in order to avoid the egalitarianism currently found in distribution to commune members.”[79] Grain production dropped, with the 1962 output at just 79% of that of 1957, and other agricultural products fell even more dramatically.[80] Tens of millions died in the countryside during these years.[81] As discussed in “Gleaning the Welfare Fields”—in this issue—survival and resistance went hand in hand as the GLF and rural institutions fell apart.[82] Cadre lost control of the rural population, which took matters into its own hands by stealing from communal stores, scavenging for food, eating the green shoots of plants before grain could ripen and fleeing the countryside. Resistance was punished, in turn, with violence and the withholding of food rations, potentially a death sentence at the time. In the wake of famine, rebuilding state institutions and Party power in the countryside would prove a very difficult task.

The Rural-Urban Relationship

The intention of the Party’s transformation of rural society and production in the 1950s aimed at building an economic foundation for the industrial development of China. This necessitated the construction of a new rural-urban relationship. The institutions of this new relationship, put in place in the mid- to late-1950s, were created to extract rural surplus, primarily through control over the grain market. As the urban population grew due to both natural increase and the free migration allowed in the early 1950s, prices rose for basic foodstuffs, at the time still primarily controlled by private merchants. This demand growth led to a rapid increase in peasant incomes through 1954.[83] Though this signaled relative prosperity, it also generated constraints on national development. While the state controlled 72% of marketable grain surplus in 1952, the next year it managed to purchase only 52% as merchants piled into the market, essentially siphoning off the tax base.[84] As the cities paid more for grain, the state’s ability to invest in expanding industrial production was restricted.

Grain-merchant profits constituted a secondary claim on rural surplus production (after that of the rural gentry) that the state aimed to eliminate. The means of eliminating this competing claim was the “unified purchasing and marketing” (tonggou tongxiao) system instituted in the fall of 1953—a crucial institutional building block of the new social formation, and the funding mechanism that made the First Five-Year Plan (and all subsequent Plans) possible. Under this system, which lasted into the 1980s, only the state had the right to buy and sell grain, and they did so with fixed prices and quotas. This meant that the state could set “prices” as they wished, controlling rural consumption and extracting rural surplus in the process.[85] Obviously, “prices” here lost the function they held in market economies, instead taking on the character of sheer quantities. Between 1952 and 1983, state purchases and agricultural taxation comprised an estimated 92% to 95% of farm sales.[86] While the amount of grain extracted from the countryside via taxes remained the same throughout the 1950s, the lowering of the price of rural goods relative to urban goods became an increasingly important form of hidden taxation.[87] Over time, the private rural-to-urban market in agricultural goods largely ceased to exist.

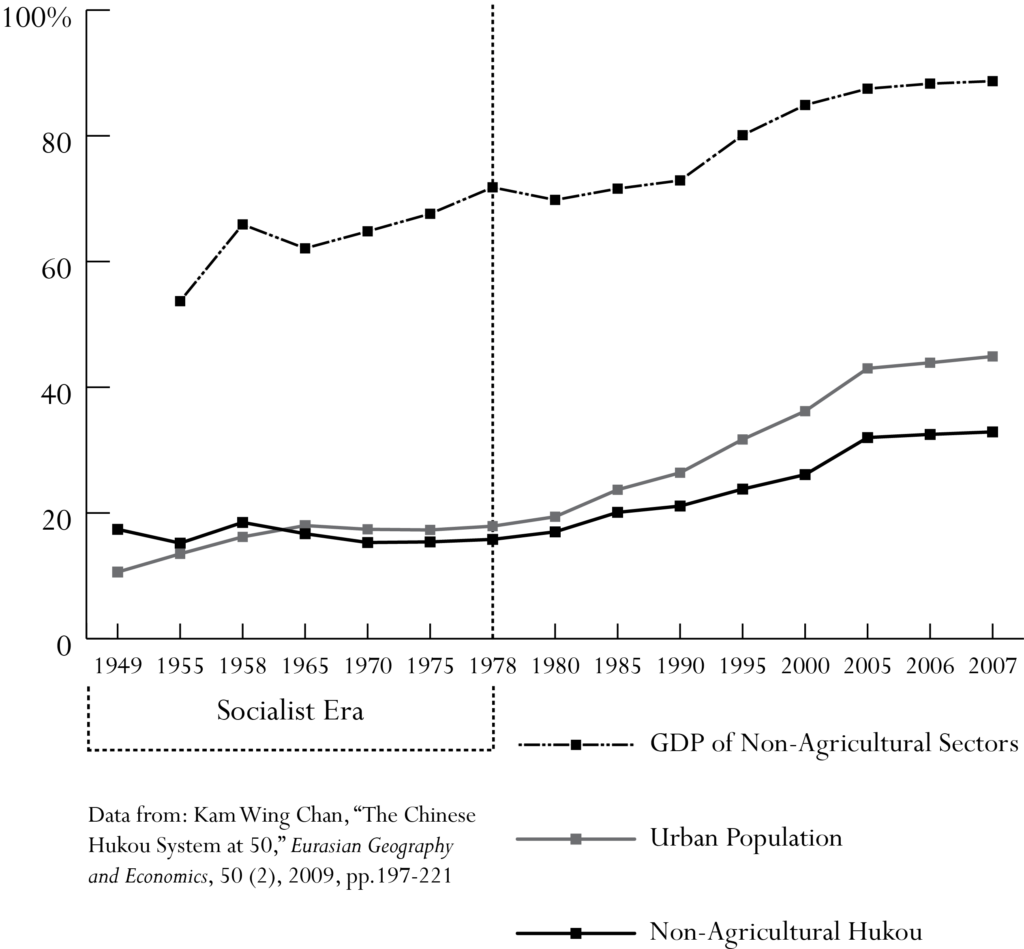

A second key institution of the new national economy was the hukou or household registration system developed throughout the 1950s. As with the new grain marketing system mentioned above, state concern over food—both for export and to feed the urban population—transformed the hukou from a relatively minimal system used to track potential enemies into a wide-ranging institution that divided Chinese into grain producers (holders of agricultural hukou) and grain consumers (holders of non-agricultural hukou). The uncontrollable flood of migrants into the cities over the course of the 1950s—first pursuing jobs in the new industries and then fleeing the famine in the countryside—provided the impetus to use hukou records to fix people in their home villages. This was achieved through the apportioning of state benefits according to one’s registration status—effectively preventing rural out-migrants from obtaining jobs in the city. Through the urban danwei system, urban hukou holders would be provided a quota of grain at a state-subsidized price, while rural hukou holders were required to produce grain and would not receive state rations, instead receiving rights to a plot of land, or a direct portion of co-operative, then collective, agricultural output.[88] With the migration crisis that accompanied the Great Leap Forward, the hukou system came to be used as the primary tool for controlling migration and the rate of urbanization, creating a sharp divide between the rural and urban spheres by allowing for mass deportations of new migrants. Unified purchasing and marketing and the hukou together with rural collectivization were the basic structuring institutions that enabled the CCP’s accumulation strategy during the socialist period, creating a fractured and unstable system that was only held together by successive extensions of the state.

The First Strike Wave

While the GLF was the first period of major unrest in the countryside, conflicts in the cities had begun to gain momentum as early as 1956, finally coming to a head in 1957 in one of the largest strike waves in Chinese history. Geographically, the unrest was centered in the coastal and river port cities, where longer-standing production networks preceded the state’s own industrialization and nationalization campaigns, and where the Chinese workers’ movement had been strongest.

In the new division of power, many of the port cities were sliding down the political and economic hierarchy. Cities such as Shanghai and Guangzhou were powerful in terms of population and production, but also relatively under-funded in the First Five-Year Plan. Nationalization in these cities entailed smaller amounts of investment than was offered newly industrializing zones and authorities were instead directed to consolidate numerous small-scale enterprises into large-scale, “joint-owned” state industrial complexes. The pre-existing industrial composition of these cities, founded on light industries such as textiles and consumer durables, further ensured their poor position relative to the Five-Year Plan, which emphasized heavy industry.

Workers in such joint-owned enterprises, then, not only found themselves lacking the privileges of their counterparts in state-owned heavy industry, but also saw the benefits they had wrested from factory owners over the past decade gradually stripped away. Under “joint ownership,” they increasingly lost their opportunities to participate in management, witnessing the evisceration of the democratic institutions that had been built within the enterprise as a counter-power to that of private owners. Many of these private owners, alongside the management personnel they had employed, were simply transferred to positions of authority within the new industrial structure, making the obliteration of workers’ own institutions all the more insulting. Maybe more importantly, the sheer numbers of managers, supervisors and other administrative personnel skyrocketed, composing “more than a third of total employees in Shanghai’s joint enterprises.”[89] This increase in administrative personnel was made necessary by the scale of consolidation and the chaotic character of the port cities’ pre-existing industrial infrastructure. Nonetheless, the practice appeared purely unproductive from the standpoint of most rank-and-file workers, instigating further resentment.

When nationalization of the remaining private firms was completed in early 1956, many workers in the new joint-owned enterprises saw their nominal wage fall, replaced only in part by new welfare benefits and piece-rate systems. At the same time, there was a sudden push to increase production as the target deadline for the First Five-Year Plan loomed. This entailed “excessive overtime and extra shifts” much of which was unpaid, as “higher-level organs approved the overtime or extra shifts requested but then refused to provide any extra money for wages, so that the enterprise had to cut bonuses and other payments to workers to make up the amount.”[90]

In addition, the last-minute rush to fulfill planning targets forced the state to ease hiring restrictions, resulting in the first “loss of control over labor recruitment” (zhaogong shikong), beginning in 1956, wherein “the Ministry of Labor decentralized recruitment powers by allowing enterprises to go through local labor bureaus rather than industrial ministries for new hires.” The result was that firms were again allowed to hire “from society,” and “the number of workers nearly doubled that called for in national plans.”[91] This new uptick in urbanization brought fresh rural migrants into the cities, began the further integration of women into the industrial workforce, and increased the strain on expensive urban infrastructure.

To put this in perspective: of the five million workers pulled into the state sector in 1956, “half were rural dwellers migrating to the cities.”[92] This trend in urbanization would be briefly reigned in in 1957, alongside the suppression of the strikes, only to explode again during the Great Leap Forward. Though the country’s urban population had been growing in increments throughout the early 1950s, between 1955 and 1958, urbanites jumped from 13.5 to 16.2% of the population, with peasants attracted by the prosperity and privilege of the cities, and then to 20% by 1960, as peasants fled the effects of famine in the countryside. After this, the new controls on population movement would see this growth essentially flatline over the remainder of the socialist period, only to increase again in the reform era.[93]

In late 1956 and early 1957, sensing the unrest and frightened by recent revolts against Soviet-backed regimes in Eastern Europe, the CCP sponsored a wide-ranging “policy of (limited) liberalization and democratization and increased scope for criticism of the Party,” in what was known as the “Hundred Flowers” campaign.[94] In standard portrayals of the period, Mao calls for criticism of the Party, and students and intellectuals follow suit. Once the movement gets out of hand, with heavy critiques leveled at the Party and comparisons being made to the rebellion in Hungary, the Party initiates the Anti-Rightist campaign later in 1957 to reign in the movement and punish those who had spoken too harshly of the leadership. There is often an ambiguity in these accounts about whether or not the Hundred Flowers’ movement had been a sort of trick to draw the Party leadership’s potential enemies out into the light.[95] But, whether a trick or an earnest attempt at reform, most of these accounts are consistent in their portrayal of the movement as a largely top-down affair, primarily involving students and intellectuals.

In reality, the Hundred Flowers campaign was a response to the extreme social conflicts that had arisen over the course of the First Five-Year Plan. It merely recognized dynamics already reaching a boiling point across Chinese society and concealed them beneath the complaints of students and intellectuals—figures who could easily be dismissed as vestiges of the old society. Directly acknowledging the antagonism that existed among urban workers would have, in effect, raised the question of whether the Party had lost the mandate of the working class. This also entailed that, after the fact, workers had to be “written out of the Hundred Flowers story as protestors, being present only as defenders of the Party during the anti-rightist campaign.”[96] But the reality was quite different.

The strikes of the Hundred Flowers year began in smaller numbers in 1956, only to explode across the country in 1957. They are put into perspective by comparison with previous rebellions, using Shanghai, the epicenter of this and earlier strike waves, as the unit of comparison:

In 1919, Shanghai experienced only 56 strikes, 33 of which were connected with May Fourth. In 1925, it saw 175, of which 100 were in conjunction with May Thirtieth. The year of the greatest strike activity in Republican-period Shanghai, 1946, saw a total of 280.[97]

In the spring of 1957 alone, however,

Major labor disturbances (naoshi) erupted at 587 Shanghai enterprises […] involving nearly 30,000 workers. More than 200 of these incidents included factory walkouts, while another 100 or so involved organized slowdowns of production. Additionally, more than 700 enterprises experienced less serious forms of labor unrest (maoyan).[98]

Workers began to draw parallels to the Hungarian rebellion, chanting “Let’s Create another Hungarian Incident!” and threatening to take the conflict all the way “from district to city to Party central to Communist International.”[99] When demands were not quickly met workers also began creating a new infrastructure through which to organize—one that started to go beyond the bounds of their individual work-unit compounds and which explicitly mimicked forms of organization that the communists themselves had used early on in the protracted revolutionary war:

[…] workers distributed handbills to publicize their demands and formed autonomous unions (often termed pingnan hui, or redress grievances societies). In Tilanqiao district, more than 10,000 workers joined a “Democratic Party” (minzhu dangpai) organized by three local labourers. Some protesters used secret passwords and devised their own seals of office. In a number of instances, “united command headquarters” were established to provide martial direction to the struggles.[100]

Nonetheless, the composition of the strikers never overcame the divisions imposed by the very industrial restructuring that had contributed to the strike wave in the first place: “some sections of the workforce, such as employees of former private enterprises, apprentices and younger workers, were much more prominent in the unrest.” This is despite the fact that “many of the grievances giving rise to protests were common to all enterprises by 1956-7.”[101] Within the enterprise itself: “Usually […] fewer than half of the workers at a factory were involved, with younger workers playing a disproportionately active role.”[102] Here the “more salient lines of division” were between “socio-economic and spatial categories—permanent vs. temporary workers, old vs. young workers, locals vs. outsiders, urbanites versus ruralites.”[103]

In some cases, this intra-enterprise division took on extreme forms and strikes were crushed by more privileged workers themselves, with no need for directives from the central government. During a dispute at the Shanghai Fertilizer Company in May 1957, 41 temporary workers who had been promised regular status but had then been abruptly laid off attacked union officials, demanding to be re-instated as regular workers. After nearly beating the union director and vice-director to death, the union, youth league and permanent workers vowed to solve the conflict themselves, and the permanent workers “even stockpiled weapons in preparation for killing the temporary workers.” Before this could happen, however, the municipal authorities stepped in and arrested the temporary worker leaders.[104]

Given the dangers posed by open worker revolt, the Party not only sided with the more privileged members of the industrial workforce—i.e., older permanent workers with urban-based families employed in heavy industries—but also sought, initially, to reform systems of industrial and political management. As early as the fall of 1956, the upper echelons of the Party had realized that the strike wave, still in its infancy, was rooted in deeper conflicts that were themselves engendered by national industrial policy. Events in Eastern Europe further verified these fears. At the Eight Party Congress the Soviet Model influenced by the five-year plans of the 1930s, with “one-man management” at its core, was rejected in favor of the alternate Soviet Model, based on High Stalinist principles, which favored mass mobilization, workers’ participation, and direct supervision and management by Party committees instead of technocratic leadership by factory directors and engineers.

Though endorsed at high levels and rendered into socialist mythology via historical comparisons with the USSR, the mobilizational policies that resulted were often more the product of local, practical solutions to factory and city-scale conflicts and, in many instances, would ultimately exceed what central authorities considered acceptable concessions to the workers. In many factories, workers’ congresses were founded, “consisting of directly elected representatives who could be recalled by workers at any time,” a form of organization that was pushed for by then-chairman of the All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU), Lai Ruoyu, who “identified democratization of management as the feature which distinguished socialist enterprises from capitalist ones.”[105]

Because of their local character, the implementation of these reforms was uneven. Workers who had implemented such changes readily accepted the formal recognition, while those in enterprises that saw less self-activity responded with distrust. Some workers refused to elect representatives to the congresses, which often had only vaguely defined powers.[106] Given that the production plans formulated at higher levels of the state remained inviolable, it was unclear how such administrative reshuffling—even if it was a true devolution of factory-level decisions to the workers—would solve the basic constraints imposed upon the enterprises. Though many Party authorities at the time, particularly within the ACFTU leadership, seem to earnestly have sided with the workers in their disputes, it was also clear that attacks on “bureaucratism” and cadre privileges produced, at best, minor improvements to the lives of disadvantaged workers, doing little to remove the concrete strains of joint-enterprise underfunding, temporary work status or production-drive overtime.

These reforms not only proved unable to meet workers’ basic demands, but also failed to prevent the rapid increase in strike activity, which dangerously exceeded the Party’s expectations. The result was a ramping up of repression against strike leaders, a reshuffling of the ACFTU leadership, and a spate of factory-level concessions that would form the basis of the next period of industrial reorganization during the Great Leap Forward.

In terms of repression, workers suffered far more than students or intellectuals. Though the crackdown on strikes was concurrent with the Anti-Rightist campaign, workers were denied the political status of “rightists.” Instead, they were given the classification of “bad elements,” implying a simple criminality rather than any sort of principled political opposition. This was no difference of semantics: “workers, and some union officials, were in fact imprisoned and sent to labour camps in the aftermath of the Hundred Flowers movement, and some were executed.”[107] When high-ranking ACFTU officials such as Lai Ruoyu, Li Xiuren and Gao Yuan stood behind the workers, even going so far as to advocate for independent unions, the result was vilification, dismissal, and a general purge of the ACFTU.

Unrest among workers continued after the end of the Anti-Rightist campaign, resulting in further concessions and significant anti-bureaucratic reforms during the Great Leap Forward. But, despite its size, the strike wave of 1956-57 never cohered into a true general strike. One of the distinguishing features of labor unrest in the mid-1950s was that it “did not have one central political grievance […] around which public opinion could be galvanized.”[108] The result was that the rebellion remained fragmented, as it was largely limited to local workplace issues. No substantial new forms of organization cohered among striking workers, nor were they able to significantly reform the existing organs of the CCP.

It is untenable, then, to simply attribute the failure of the strike wave to the state’s repressive measures. For the most part, the state simply did not have to intervene. Divisions within the workforce—particularly along lines of seniority and regular versus temporary status—were often sufficient to prevent the strikers’ demands from galvanizing wider support. The striking workers were often the minority in their own enterprises, and their demands were just as often violently opposed by other workers, as in the example of the Shanghai Fertilizer company.

The Party would soon leverage this fact, portraying strikers as “bad elements” with non-proletarian family backgrounds attempting to trick other workers into participation in an anti-communist conspiracy. Despite the exaggeration of this propaganda, the kernel of truth here was simply that a significant bulk of the national industrial workforce was sufficiently satisfied with their positions to be wary of losing them. This was especially true among the older workers, who not only held higher wages and received more benefits, but also remembered the abysmal conditions of work prior to the revolution.

The divisions that prevented the strike from generalizing were also the product of uneven geography. Cities like Shanghai were unique in their high percentage of less privileged “joint-ownership” enterprises, whereas newly industrializing areas and the Northeastern cities had a higher proportion of state-owned heavy industrial enterprises, and therefore received a greater share of the net surplus over the course of the 1950s. Despite Shanghai workers’ noticeable decline in wages and benefits, then, national trends were either ambiguous or opposite. At the national level, “per capita foodgrain production and nutrient availability peaked in 1955-56,” and a disproportionate share of what was produced during this peak was given to urban industrial centers, rather than the peasants who had produced it. This share dropped slightly in 1957, but it was not until the disastrous policies of the Great Leap Forward that most urban centers would see a true decline in living standards.[109]

Origins of the Great Leap Forward in the Cities

The industrial policies of the GLF can be understood as a somewhat haphazard response to several budding crises in the economy. Despite success in pausing the transition to capitalism, the early stages of what would solidify into the socialist developmental regime were ultimately forced into a mechanical mimesis of the dynamics they had sought to overturn. Nearly half a century of periodic war had ended and the average person’s livelihood had improved, but the concessions given to the urban workforce were beginning to limit the amount of surplus that could be extracted, second-hand, from grain-consuming industrial workers, thereby hindering the expansion and modernization of industry. At the same time, the 1950s had seen the number of state administrative and technical personnel skyrocket well beyond its planned budgetary restraints, further limiting the surplus available for investment.